When the menu flaunts four types of avocado toasts including one that combines pickled red onions with creamy almond butter that you can wash down with lavender or honey bee latte, you’re probably in a California cafe. Should faces with beards and nose rings outnumber wrists with Apple watches, you’re not in Silicon Valley. If the dude behind you in the line is nestling an eight or nine-foot surfboard in bronzed arms emblazoned with a deep blue tattoo that continues under his hooded shirt before emerging on the other side to complete the picture, you’re in Santa Cruz, baby!

It’s eight in the morning at the 11th Hour Cafe in downtown Santa Cruz and yes!… I order an avocado toast along with a merely plain coffee and set up by the entrance on a bar stool against a polished pine-slab tabletop—just where I can see the patrons as they wander in and order at the all-girls counter, before getting situated. Which they can with plenty of options, for this cafe has seating everywhere: outdoors at the front, where a woman in a green shawl and absurdly tall platform slippers sips her coffee above a golden retriever that waits calmly at her feet, a massive snout resting on broad paws; a large room out back with wooden tables and chairs and a few sofas; and even an outside patio. But we aren’t done.

There’s a coffee roastery at the back, a dimly-lit full bar with high-gloss dark wood veneer that looks primped for an evening act, and store merchandise all over that includes t-shirts, hoodies, ceramic mugs, and assorted coffee gear. Potted green cacti and ferns sprout randomly, like mold on a bread slice. An ancient wooden upright piano broods in a dark corner.

Early that Sunday morning, I had ridden down to the town of Los Gatos to take California Route 17 connecting San Jose with Santa Cruz, across the mountains. The road has few cars out this early but will be jam-packed by noon with families driving down to the beaches and further beyond into the towns around Monterey Bay, eager to be shocked out of their Covid stupors by the cool April mountain wind and the frigid Pacific water.

The highway weaves left and right, with sharp turns and teasing curves as it finds the easiest path through the mountains, like a river yearning for the ocean. Route 17 was built in the early part of the 20th century and was relaid after 1950 when the Lexington Reservoir was created, inundating the towns of Lexington and Alma through which the highway passed.

You notice things on a motorcycle that you never do when you have a roof over your head or pillars bisecting your eyes. The asphalt hurtles faster towards you, the trees loom higher even as the sun plays hide-and-seek behind them, and the wind buffets your head in an unabating reminder of true speed.

Yet you see more and everything looks a bit bigger when there’s no frame around it: hills, ravines, streams, cattle, and the smudged faces of little kids flattened up against car windows as you roar by and offer a friendly thumbs-up (with your left hand please, or you will kill the throttle!)

A motorcycle has multiple controls—a clutch, a hand brake, a foot brake, and gears—creating enough work for every limb to stay busy while coordinating closely, but no control is more important or underrated than the one under your right wrist—the throttle.

A smooth ride has everything to do with a smooth throttle. Rolling off the throttle closes the throttle control value that regulates the amount of air that gets into the engine. As the valve closes it creates a low pressure at the intake of the engine, making the cylinders have to work much harder to compress against a partial vacuum. This saps their energy, drops their power, and rapidly slows down the bike through engine braking. Meanwhile, the engine control unit (or ECU) that constantly monitors the throttle position sensor and a host of other sensors, has already instructed the fuel injectors to starve the cylinders by cutting off their fuel.

Dropping a gear, further amplifies the braking by increasing the engine speed (rpm) even as fuel remains shut off. This creates even more resistance against the pumping action of the pistons which causes the bike to slow down yet further. Modern motorcycles have powerful high-compression engines that react rapidly to very small changes in the throttle.

The opposite happens when that right hand opens the throttle: the bike surges ahead, eager to pass everything. A throttle opened up at low speed with the clutch pulled in and suddenly let out, can deliver power so instantaneous that the forces can swing a bike around its center of gravity before the tires can bite into the ground, causing a wheelie where the front wheel lifts clear off the ground, like a bucking steer trying to lose its rider. A good rider can cross mountains by just controlling the throttle and without ever touching the brakes, if only he could check the juvenile enthusiasm of his fidgety right hand.

I’m betting that Hollywood tough guy, Will Smith—he with that twitchy right arm—wouldn’t be the one to do it.

I leave the cafe late morning and ride down towards the ocean looking for Beach Street, where I turn and climb up onto W Cliff Drive that ascends along the edge of a cliff, away from Cowell Beach below me.

To my left, the Santa Cruz wharf runs over eight hundred meters out into the open ocean, as the longest pier on the west coast. It hosts restaurants, gift shops, and wine-tasting salons above, and sea lions below, that rest in the wooden rafters and let everyone know. I pull up at the Lighthouse Field State Beach, at the tip of a broad promontory where the road starts to turn inwards again, park the bike, and walk over to the edge of the cliff above the water.

Below me, for hundreds of meters on either side are surfers—riding waves, paddling back to catch the next one, or simply resting atop the surging water to recover from their exertions. This is Steamer Lane, among the most famous surfing locations on the west coast and one of the best places to ride the quintessential North California wave. It has four zones running left to right that generate different waves and surfing experiences.

The wetsuit was invented here in the early 1950s and is often credited to Jack O’Neill—a body surfer and World War II navy pilot—although the inventor was more likely Hugh Bradner, a physicist from the University of California at Berkeley who arrived at this neoprene invention when he studied the problems encountered by frogmen in frigid waters.

I’m guessing male shrinkage wasn’t one of them.

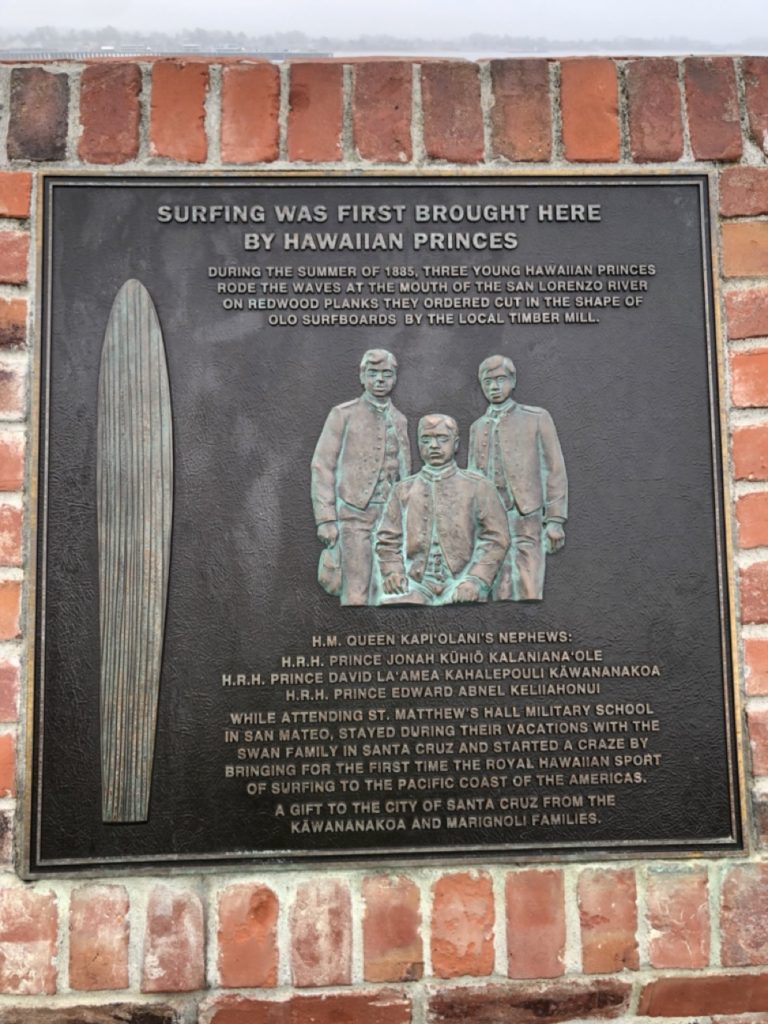

Surfing was brought to California in 1885 by three Hawaiian princes who rode the Santa Cruz waves on surfboards crafted with Santa Cruz redwood. Surfing likely originated in the south Polynesian islands before it made its way to Hawaii and consumed its idle and bucolic royalty. I walk by the Surfing Museum where a plaque illustrates the story. The brothers took their original surfboards back to Hawaii. More than a hundred years later, in 2015, the boards were brought back to Santa Cruz for a historic visit.

I start up the Triumph and ride across town—past gas stations, Mexican restaurants, Chinese takeouts, closed real estate offices and art studios, to get back onto highway 17.

Miles later a white Ferrari screams past, doing at least thirty miles over the speed limit as it swings around in a wide curve. I can proudly tell you that my right arm didn’t even twitch.

great story love all the details!

I am feeling so nostalgic for Santa Cruz, my hometown. Thank you Vijay for this beautiful portrait and I learned so much about motorcycles, having only ridden in the back of one many times but never driving one myself.

I look forward to reading about your next adventure!

It’s hard to overlook how different Santa Cruz is from the Bay Area, although merely an hour away.