The Younger Gang—outlaws and co-conspirators of the infamous Jesse James—once hid out here, presumably with their stash. Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters lived communally in a redwood cabin here where they held their light-and-sound psychedelic LSD-fueled parties, seeking to expand the consciousness of mankind. Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—chronicle of the roots of the hippie movement and among the best-cited works of the New Journalism style—got its raw material here. The Grateful Dead played here. Which means the Hell’s Angels rode in on their thundering motorcycles. Hunter Thompson and Neil Young lived here too.

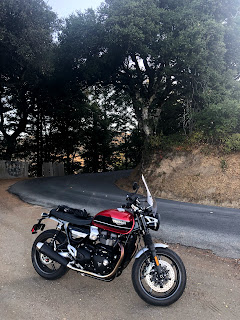

I’m in La Honda—a tiny forgotten mountain town with less than a thousand residents—that I reach around nine on a recent morning. The ride, along Alpine Road, winds west for many miles over long stretches of frequent tight turns through nature preserves and creeks, leaving the motorcycle raucous and impatient in second gear.

I’m in La Honda—a tiny forgotten mountain town with less than a thousand residents—that I reach around nine on a recent morning. The ride, along Alpine Road, winds west for many miles over long stretches of frequent tight turns through nature preserves and creeks, leaving the motorcycle raucous and impatient in second gear.

At low gear and speed, a motorcycle gets hot very quickly and will dutifully let your legs know. Early motorcycle engines were air-cooled and depended on metal fins around the cylinders to stick out into the airflow to give up their heat. Then liquid cooling came along using water’s superior thermal properties over metal to soak up engine heat. But liquid cooling needs a big radiator up front to dissipate heat from the water itself and that mucks with the aesthetics of motorcycle minimalism. It is for this reason that most Harleys are still air-cooled even as their riders atop are willfully slow-cooked, like the frog in the fable. Harleys also persist with V-twin layouts that puts one unlucky cylinder at the rear and in the hot slipstream of its happier twin ahead.

Bad science! Bitchin’ sound!

I stop at the La Honda Market—the town’s only store—with supplies, beverages, and a sandwich counter that looks barren. A man in a blue plaid shirt takes my money and points to the large coffee carafe.

I stop at the La Honda Market—the town’s only store—with supplies, beverages, and a sandwich counter that looks barren. A man in a blue plaid shirt takes my money and points to the large coffee carafe.

Tiny 50 oz. bottles of Jack Daniels and Smirnoff stand tidily against each other like soldiers in a parade, ready to move for $2.99 each. A framed old poster on the wall offers a $500 award:

Wanted Notorious Outlaw—Belle Starr.

Belle Starr was a rare woman outlaw from the post Civil War period and an associate of many of the notorious Missouri-born criminals, including the Younger Brothers who had moved to La Honda. But she must have lacked their keen bloodlust, for the poster warns us thus:

“Though not a killer she is known to carry two Pistols and has a reputation for being a Crack Shot!”

Shot to death at the age of forty-one, Belle Starr lives on in many movies, books, and songs from musicians like Woody Guthrie and Mark Knopfler.

Shot to death at the age of forty-one, Belle Starr lives on in many movies, books, and songs from musicians like Woody Guthrie and Mark Knopfler.

I take my coffee to the small porch outside and settle down on one of the tables overlooking the road. The coffee lid frustratingly lacks an air vent and the enjoyment from the beverage is rudely annulled by my constant anxiety from trying to get at the coffee while fighting a possible spill at every sip. Tired of fighting nature’s abhorrence of a damn vacuum, I finally remove the lid and throw it away.

A cyclist pulls up, leans his bike against the rail, and goes in. Two large water bottles sit on the triangular bike frame, like V-twins on a Harley. He comes out with a sandwich and I find a way to start up a conversation. Turns out that he’s on an 85-mile bike ride today that will take him across the mountains, to the beach and then back again—which I believe might partially explain why he didn’t come out brandishing one or more of them 50 oz. bottles for two-ninetynine apiece. But he makes me curious about the fuel requirements for his arduous trip and so I ask him what he’s eating.

“Ham and cheese is what I usually get, but they are out of it today. Don’t know what this one is,” he says as he peels back the wrap and digs in. Small semicircular cutouts appear rapidly on the round fat bun that soon disappears.

“Ham and cheese is what I usually get, but they are out of it today. Don’t know what this one is,” he says as he peels back the wrap and digs in. Small semicircular cutouts appear rapidly on the round fat bun that soon disappears.

We leave together and I’m happy to be the one on the motored bike. He slips his feet into clipless pedals to become one with his bicycle, waves and rides away with striking ease.

I cross the street and walk over to the rustic shack diagonally across. This is Apple Jack’s—a roadhouse and watering hole—that has quenched bandits, horsemen, stagecoach travelers, beatniks, bikers, hikers and techies, over 142 years. The facade wears an exhausted droop and the tall redwoods that surround and dwarf it appear to have taken over the responsibility to prop the place up and keep it standing. The saloon still comes alive every weekend with live blues, rock, and country music that floats around, adding bounce to the dusty feet dancing away on the creaky floorboards, before wafting down the mountains and dissipating into the valleys.

I get back on the bike and ride down a narrow side road looking for Ken Kesey’s restored cabin, but can’t find it. Kesey was supposed to have written parts of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, his first novel, on the bathroom walls and I wonder if they might have been preserved. The road ends at a trailhead leading to the newly created La Honda Creek Preserve and I disappointedly turn the motorcycle around and ride back out.

I head out north for a few miles on highway 84 to get to the junction with highway 35, marked by the iconic Alice’s Restaurant—a building from the early 1900s that was turned into a restaurant in the 50s and proclaims to be “little slice of bliss among the redwoods”. Motorcycles and low-slung sports cars fill the irregular lot in the middle of the four-way junction that it occupies. A single retro gas pump with an analog readout gurgles away, in stark contrast with a biker in a mod red-and-white leather suit fueling his fiery red Ducati.

I turn south onto Skyline Drive and follow the road over the ridge of the mountains for about fifteen miles, before descending down in a flurry of bends.